Teaching to the test

Benjamin Wann

Teaching to the test

On October 19, 2009, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution broke a story with the provocative title "Are Drastic Swings in CRCT Scores Valid?"

The CRCT acronym referred to the Criterion-Referenced Competency Tests, which were, as the article specified, "Georgia's main measure of academic ability through eighth grade." The report questioned the spectacular yet baffling improvement in the student CRCT scores at several Atlanta-area schools. Perhaps the most damning analysis in the report demonstrated that the likelihood of such incredible academic progress was less than one in a billion.

Something was fishy.

You see, when officials drew up the CRCT tests, they implemented the typical carrot and stick approach. It was a carrot for teachers whose students met their score-improvement targets, particularly those at Atlanta-area schools, where such performance qualified teachers for bonuses of $2,000 each.

The stick was that teachers with low scores would face increasing oversight and could potentially lose their jobs.

When challenged, teachers, principals, and superintendents insisted that the massive improvements in scores resulted from better practices. Still, an investigation found that nearly 180 educators had engaged in cheating activities across forty-four Atlanta schools, including providing correct answers to students and correcting student answers.

When the investigation concluded, twelve educators were criminally tried, and at the end of a long and embarrassing trial, eleven were convicted, nine of whom served jail time.

So, What Happened?

Results on standardized student tests were used as the proxy for educational outcomes.

By evaluating teachers on their students' test results and holding the teachers accountable for producing acceptable results, the federal authorities responsible for managing education would be able to identify consistently underperforming teachers and schools and have a publicly sufficient rationale for taking disciplinary actions.

As the state's proxy for educational attainment under the previously discussed No Child Left Behind Act, CRCT scores represented both a stick and a carrot. It was a stick for Georgia schools' teachers, principals, and superintendents whose students performed poorly on the test. They all received negative reviews and added scrutiny.

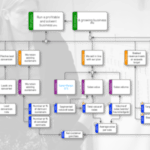

No Child Left Behind As of the turn of the twenty-first century, there was a growing concern that, on average, American K–12 students were falling behind those of other leading nations. The desire was to improve educational outcomes for American students to support the global competitiveness of the American economy in the twenty-first century. The underlying metaphor was that of the negligent parent.

The cause-and-effect model built upon the theory that America's performance lagged because both schools and the teachers (the parents in the metaphor) were not being held accountable for delivering strong educational outcomes in the K–12 system, a system mainly funded with American tax dollars.

Teachers' efforts and attention to the task were variable, and the weaker schools had neither the will nor the power to enforce standards and improve the work of underperforming teachers. If the federal government stepped in and enforced accountability—that is, forcing those negligent parents to pay attention—the variability would diminish, and the average outcome would rise meaningfully.

What We've Learned

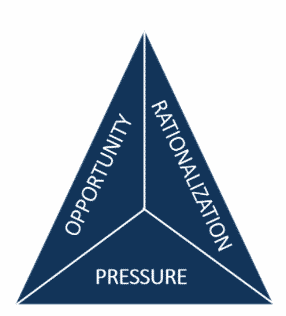

The aftermath of the Georgia standardized test cheating incident underscores the importance of being more mindful of setting effective KPIs. As we reflect on models like the Fraud Triangle, this incident showed us how the circumstances led to students' unethical behavior and poor outcomes. Teachers were under pressure to improve student scores in a district with poverty-stricken students and a lack of appropriate resources. Failing would cost them their jobs.

The teachers also had the opportunity to review test submissions before being sent to be scored, and they could revise and change answers to meet specific metrics. And finally, teachers rationalized that helping students cheat would allow them to continue through the educational system and not get left-back, increasing their chances of graduating.

When we have a goal in mind, we must create incentives that properly guide the desired behaviors. Bernie Smith's book, GAMED, and teaching add value here in the concept of black and white hat testing. Administrators can learn what participants may and may not do by designing and testing incentives with test groups. Then, as feedback is collected, metrics can be further refined until the optimal model is determined.