The incentive theory of motivation

Why the motivation model we all use is broken

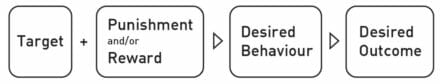

There is a seductively simple model that most of us use for targets, incentives, and behaviour. The logic goes like this…

If we want someone to do something, we set them a target and offer a reward for achieving that target or punish them for not achieving it.

Put a little more reductively…

[Target] + [Reward for hitting target] and/or [Penalty for missing target] drives [Desired behaviour] which delivers [Desired outcome]

Everybody from parents of young children through to reforming governments invest a huge amount of time, effort, and energy based on the assumed truth of this model.

- If the target is important, we offer a valuable reward, often money (these are called extrinsic rewards).

- If we really want them to achieve the target, we offer them a bigger reward.

- If we want people to over-perform, we offer additional financial incentives.

Whether it’s banks offering bonuses to their staff or governments incentivising couples to have children, this approach seems to be hard-wired into most business models and even our personal lives.

The risk of using high-value incentives

There are two major risks that come from using classic incentives where the reward has high real-world monetary value or extreme reward and recognition (think ‘winning the Olympics’, officially the only reward is a medal, but in reality the rewards are much more tangible and often financial) .

Classic reward incentives often do not work and frequently have the opposite effect from the intended one.

Highly desirable rewards can drive cheating, use of loopholes, and even law-breaking. Policing high-value incentives can introduce an extra level of stress, complexity, and cost.

Why do rewards often fail, backfire and become difficult to run? That’s what we will explore in this post.

The two types of motivation

Intrinsic and extrinsic rewards and motivation: their critical differences

Our classic model assumes a particular type of motivation, called ‘extrinsic’ motivation. This type of motivation is the sort that comes from external reward (sometimes called and extrinsic reward) or punishment. The logic is that if you offer a big enough reward, it drives someone to do something that you want them to do. Let's take a look at intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, and their risks and benefits...

Extrinsic reward examples

Examples of extrinsic rewards might include...

- A cash bonus

- Promotion

- A new games console

There is another type of motivation, the sort that drives amateurs to…

- Complete a tough non-competitive run

- Climb a mountain

- Learn an instrument

These are complex, demanding tasks where the rewards are non-financial and usually come from within the individual. These people are prepared to put hours of training and effort into something where the reward is entirely internal. We call this an intrinsic reward.

This type of motivation is called intrinsic motivation. It’s the sort of motivation that comes from personal challenge and the satisfaction that arises from meeting that challenge.

Intrinsic rewards examples

Examples of intrinsic rewards include...

- Pride in your work

- Feelings of respect from supervisors and/or other employees

- Feeling that what you are doing is worthwhile and has purpose

- Feelings of accomplishment

- Learning something new or increasing competence in a specific area

- Being able to choose which projects you work on

- Enjoying working as part of a team

An intrinsic reward comes from within the individual.

Why external reward (or punishment) is not always a good idea

There have been many psychological experiments on the relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and their results uncover an interesting and surprising risk.

In the 1973 Stanford experiment by Lepper, Greene and Nisbett, researchers decided to see what impact external reward had on a ‘fun’ activity for a group of preschoolers.

They came up with an optional activity that they had previously shown kids would be interested in: using felt-tip pens and a big pile of paper to draw pictures.

The experiment had three groups.

The first group, the ‘Expected award’ group, were told at the start that they would be given a ‘Good player award’ for their drawings, once the six minute session was complete.

The second group, the ‘Unexpected award’ group, were awarded a ‘Good player award’ after drawing a picture, and were given no advance warning of a reward.

The third group, the ‘No award’ group, were simply allowed to draw with no award promised or given.

During the experiment, children who were in the ‘Expected award group’ scored worse during the test (on ‘blind quality’ scoring) and after the assessment showed a reduced interest in the activity that they previously enjoyed, compared with the other two groups.

The introduction of the promise of external reward before the activity worsened performance in the short term and reduced interest in the activity in the longer term. The researchers gave this effect the name ‘Overjustification’.

In another study of the effects of rewards on the motivation of adults, by Edward Deci in 1971, students were asked to do a puzzle (with the competing lure of magazines on the table next to them). The experimental group worked for three sessions and were paid on a ‘per solution’ basis in the second session. Their motivation was measured based on their engagement with the puzzle during ‘downtime’ when they didn’t realise they were part of the experiment.

The results showed that when reward money was involved, intrinsic motivation declined. When ‘verbal reinforcement and positive feedback’ was used, motivation increased.

This study suggests that the type of reward also has an impact on intrinsic motivation.

The message here is that any type of reward has the potential to undermine a person’s inbuilt (intrinsic) interest in an activity and monetary rewards can have a particularly harmful impact.

The cost of incentives

A tale of two events

Running is a popular sport. It has a low barrier to entry and is probably the oldest competitive athletic activity. It’s also a useful lab to compare two very different approaches to incentives.

Olympic running

Anyone not living in a cave for the past hundred years will be aware that running is a major part of the Olympics. The 100m sprint and marathon are centrepieces of the event. Victory in the Olympics can bring immense fame and fortune. The sprinting legend Usain Bolt is estimated to have a net worth of over $90 million.20

In the 2018 Winter Olympics timekeeping was handled by 300 timekeepers, supported by 350 trained volunteers and 230 tonnes of equipment.21 Performance-enhancing substance testing was run by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), which had an annual budget of $32 million (2018) and employed 117 full-time staff. 22

Parkrun

At the other end of the spectrum is a UK grassroots running movement called parkrun. Across 700+ UK locations, thousands of runners head to their local parks each weekend to run (or walk) timed 5k races. There’s no fee and the only reward is a free t-shirt after 50, 100, 250 and 500 races and a record of your race time on the parkrun website. It is run by thousand of unpaid volunteers.

Timekeeping is handled using (optional) personal bar codes to log your time with a scanner-wielding volunteer at the end of your race. The only performance-enhancing substances found on parkrun are usually coffee and homemade cake. Needless to say, there’s no testing programme for this.

And the difference is…

The core activity of both movements is the same: running. The difference lies in the types (and magnitude) of incentives and rewards on offer. Although the Olympics was designed originally for ‘amateurs’, it is no secret that winning a high profile event brings international fame and riches (afterwards), extrinsic rewards. These extreme rewards have driven behaviours that have led to the need for multi-million dollar timekeeping and anti-doping measures for elite sports around the world. For parkrun, there are no prizes beyond a token free t-shirt for 50+ runs and the satisfaction that comes from running a good time, so intrinsic rewards. There is no fame or fortune attached to an outstanding parkrun. Activities that are based on intrinsic motivation, like parkrun, are far cheaper and simpler to police than activities with substantial material rewards, such as a flagship Olympic event.

Incentives and the baggage they bring

Incentives can stimulate dramatic responses. Whether it’s the prospect of earning lots of cash, fame, or the threat of dire consequences, some people will take much more extreme measures when there is a strong incentive or punishment in place.

Put simply, the bigger the reward or penalty the greater the likelihood of…

- Loopholes being identified

- Rule-breaking

- Law-breaking (in extreme circumstances)

Of course, it’s possible to tighten the rules, police those rules more carefully and create deterrents to offset the temptation to cheat, but this all takes time, effort, and money. As any fan of motor racing will also know, it’s rarely a static situation. Racing teams constantly test the limits of the rules in new and creative ways, leading to a kind of ‘arms race’ when it comes to creating and flexing maker’s rules.

Any major performance-based incentive will bring with it a significant cost of policing and enforcement, in addition to the costs of the incentive itself.

Serious extrinsic rewards bring risk

Larger extrinsic incentives do not just bring greater enforcement cost and complexity, they bring additional risk. No policing system is perfect, so we must ask:

What risky behaviours and outcomes may be incentivised by this? And, what are the reputational, legal, and moral implications of those risks?

As we saw in our earlier case studies, these risks can sometimes be measured in terms of employee years in prison, avoidable deaths, or losses of tens of billions of dollars.

Your single most important incentive design decision

This is the most important decision you will make when you are setting up targets with the intent to motivate employees, perhaps striving to increase employee engagement -

‘Will you offer a reward with significant monetary value or prestige for achieving the set targets?’

This single decision, on whether to use external rewards and whether they are of material value, will have a profound effect on how your targets and incentives function, whether they deliver the intended results, and repay the effort required to manage them. Remember, significant extrinsic rewards are potentially very risky and can often drive unexpected behaviours.

If you do decide to go ahead and use external reward, particularly extrinsic reward, make sure you use the ROKET-DS Incentive Design process to maximise you chances of a positive outcome and achieve your ultimate objective.

Relevant articles...

What Are KPIs for Sales (and What Does KPI Stand for in Marketing)? Everything You Need to Know

Dashboards are packed with numbers, but not all numbers are KPIs. If you’ve been asking yourself “What is KPI in sales and marketing?“, here’s what it means – and why copying a list of KPIs from the internet might not get you the results you’re looking for. Sales and marketing teams love numbers. They fill…

What Are Terms of Reference? (Free Terms of Reference Template)

We answer what are terms of reference, why they matter for meetings, and how they connect to reports & dashboards. Free download: terms of reference template.

Dashboard Design Checklist for Better BI (54 check points!)

Make your reports easier to read, nicer to look at, and more useful. Let’s be honest-most KPI reports are either a hot mess or just plain dull. If you’ve ever looked at your own report and thought, “Why isn’t this working?”… this is for you. What Is the Dashboard Design Checklist? It’s a comprehensive list…